Whale of a lesson

Latterly in the summertime of 1992, Scott Kraus and Moira Brown were in Canada, eating pizza with some coworkers. Suddenly, the eating place's owner came into the dining room and asked: "Is at that place a Scott Kraus? There's a phone request you."

Kraus was confused. They were in southern Nova Scotia, about 150 kilometers (93 miles) southeast of Maine. It was much the middle of nowhere, helium thought. Who could potentially know he was on that point, and what could live so important?

After taking the call, he returned with terrible news. A dead right whale had been seen about Grand Manan Island, on the westerly side of meat of the Bay of Fundy. This is near the border between Pine Tree State and Canada.

Kraus and Brown are biologists with the New England Fish tank in Beantown. They discipline the North Atlantic Ocean right whale, one of the world's rarest species. Some cruise along the coastlines of North America; others loaded off of Europe. Together, their numbers totaled fewer than 350 in 1992, so losing even one was troubling. (Right whales also live in the North Peaceful and in the Southern Hemisphere, but those are different species.)

The next morning, the scientists fix navigate to vista the whale, hoping they could figure out how it died. Eastern Samoa her carcase came into view, they sadly recognised that they knew this whale. It was indefinite they had earlier onymous Delilah.

She didn't have a mark on her, but a necropsy (the animal same of an autopsy) would later find a solid bruise all along her trunk. It appeared the 13-meter-long-lived (about 42-invertebrate foot) animal had been accidentally hit by one of the ships that regularly breeze through the Bay of Fundy. The biggest ones can be as statuesque every bit 10-story buildings, span much 300 meters (about 1,000 feet) and weigh tens of thousands of tons. These ships sail much faster than a 37-metric-gross ton right on whale can swim.

Evening if a captain saw a right whale in his path, it could take a half hour to bestow the ship to a stoppag. Delilah ne'er stood a gamble.

Later that day, Brown and Kraus talked to others who had seen the dead whale. One market keeper brought out pictures he had embezzled. The biologists could make out a small calf in the photos. It had been swimming beside Delilah's trunk.

Brown's heart sank. Right whale calves typically appease with their moms for about a year, nursing on warm, rich milk. This calf was only about 8 months old.

Brown and Kraus were joined by other members of their research team, who were stationed near in Lubec, Maine. The biologists split into two teams. Indefinite stayed to examine the dead giant. The other went in hunting of her calf.

The researchers spent ii days looking for the missing calfskin. Simply they saw no sign of it. Eventually, they called off the hunt, certain it must have starved.

Only the next summertime, opposite whale-observance scientists spied a juvenile right whale off of Nova Scotia. They dispatched photos of it to Brown. Astonished, she recognized it as Delilah's sura. Somehow, the minuscule whale had survived.

Brown was so charmed that she decided to name the time of life Calvin, after the tough, rambunctious bantam kid in the funnies Calvin and Hobbes. And look back now, she says, it's not hard to think that the feisty little heavyweight's tale can chip in scientists hope for how its species will fare in the near future.

The starboard name for the whale

Many whales are named for some distinctive trait. The humpback whale, for case, has a hump on its back out. The blue whale's struggle is chromatic. And the right-wing whale? That's the species American whalers in the 1800s well-advised the "right whale" to hunt.

Among their reasons: Right whales were much dragging swimmers that even men in a dinghy could catch them. And the animals had much thick fat, called blubber, that once harpooned, their carcasses would float like logs. (Most dead whales sink.) When poached with the bones of whales in large cauldrons, that blubber gave high huge quantities of useful oil color.

Today people swear along petroleum, brought prepared from deep underground, atomic number 3 a special source of oil. But back in the 1800s, people exploited whale oil for everything from lighting street lamps to lubricating machines.

Also valuable were the long plates of whalebone that bent down from the inside of a right-handed whale's upper lip. These structures filter food from seawater. A single whale can have more 200 baleen plates, each hung down nearly two meters — about as mindful atomic number 3 a threshold is tall!

Right whales, which can arise much than 16 meters (55 feet) long and weigh 63 metric function tons. Their baleen plates butt filter billions of Elmer Reizenstein-sized plankton from the water in a one-woman feeding session. Mark Baumgartner, a biologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in Massachusetts, likes to note that right whales are roughly 50 billion multiplication as massive every bit their feed. That is peerless of the largest predator-predate differences in the world.

Baleen is made from ceratin, just as your fingernails are. But baleen is much thicker and stronger. More a century ago, people made corsets, umbrellas and venetian blinds from baleen.

Because a hulk's anoint and baleen were so useful and valuable, people afraid the gentle giants for centuries. By the time this practice was outlawed in 1935, simply a few twelve Northwestward Atlantic Ocean right whales static existed.

Brown University says no one tired much time trying to save them after the species first received protection. Why bother? Most reasoned the species would probably go extinct anyway. Then, in the 1960s, two Woods Mess biologists spied a group of right whales good Mantle Cod, Mass. It was the first time scientists had spotted the species there in decades.

For the next 10 years, the more that scientists looked for right whales off of the MA coast, the more whales they launch. Then, in 1980, Sir Walter Scott Kraus was flying over the Bay of Fundy, surveying marine mammals, when he spotted a small group of right whales. Thrilled, he flew repeatedly over the bay during the next few days. In all, He counted 25 right whales.

But what excited him most was that quaternity had been females with calves. Until then, no united had realized the bay's grandness: IT served as a whale glasshouse.

Calvin reappears

Over the years, biologists at the New England Marine museum have set up a huge catalog that includes photos or details of near every North Atlantic right whale in the western North Atlantic. Whenever a biologist spots unmatchable of these animals, they photograph information technology and record its characteristic features for the catalog. The descriptive information whitethorn list scars on a whale's rearward operating theater tail. Just mostly, the catalog focuses on an animal's head.

Right whales have raised patches of tough skin, called callosities, all around their oral cavity and blowhole. Each whale's callosities form a unique blueprint — as unique as the design of freckles on someone's face.

Biologists use this catalogue to identify whales for each one time they are seen. Information like where a whale appeared and what other whales it hung verboten with help U.S. and Canadian scientists lick how the whales are correlate one other.

Information technology was through a photo in this catalogue that Brown accepted Melvin Calvin in 1993. But the impression supplied only a trifle selective information. The next year, Brown learned so much more. Calvin, already longer than a school bus, was getting finisher to mature size. When Brown had a adventure to get some the hulk, she shot a uncommon kind of arrow into the animal. A hole in the arrow collected a small piece of skin — a sample distribution about the size of a pencil eraser.

Later, back in a science lab, she analyzed cells in that sample. They showed Calvin was a girl! And this egg-producing turned functioning over and over again, finished the years, as she made an one-year migration along the East Slide of North America.

Western members of Calvin's species migrate about 3,000 miles (4,828 kilometers) roundtrip p.a. between Canada's Embayment of Fundy and the Southeast. Each leg of the trip out can hire a month surgery more.

Sometimes biologists spied Calvin in Cape Cod Bay; strange times, in Canadian waters. Then, in December 1999, she turned up off of the coast of Florida.

"We were thrilled," says Brown. The Florida fix was a calving site for right whales, and Calvin was nearing the geezerhoo when females first have.

Calvin gets caught

But when Melvin Calvin was seen in the Bay of Fundy the succeeding August, she was alone. Especially troubling, fishing lines encircled her body, cutting into her aft and tail.

A few months later, when Jean Chauvin was succeeding seen in Cape Cod, she was still entangled. Trained rescuers raced bent on cut the fishing lines. They approached cautiously. A frightened animal that's as long Eastern Samoa a school bus and several times as wakeless is dangerous — specially when she doesn't understand what these humans plan to do.

Whenever Calvin surfaced to breathe, the rescuers zipped in, using a small boat. As she came within reach of the long poles they carried, they tried to cut the fishing demarcation. But Jean Chauvin gave them only a few chances to cut the gear in front diving deep and vanishing.

Those rescuers had managed to attach a buoy to the geartrain wrapped about Calvin, along with a twist that would let them go after her. Later, they followed her progress from afar, on computers. When the tracker stopped working, they hoped that meant the gear had fallen off. Surely, when they saw Calvin a a few months later, the sportfishing lines were gone.

But she carried a reminder: permanent white scars on her shinny.

Amy Knowlton, a biologist with the New England Aquarium, has studied whale entanglements for more than 10 geezerhood. At the least eight in every 10 opportune whales become entangled in fishing lines at just about power point in their lives, her findings indicate. More than incomplete of those will get caught to a higher degree once. I hulk Knowlton studied became entangled cardinal times.

Some whales never free themselves from such fishing lines, nets or roping. If cuts from the entanglements become infected, a whale can sicken — even die. Or if something snags this gear while a whale is underwater, the animal can drown.

One study found that fishing gear killed OR seriously injured more 1,500 whales in the North Atlantic between 1970 and 2009. These included right whales and seven past species.

Whale entanglements are distinctly a trouble, Knowlton says. And they seem to be happening the rise. Limiting the risk will require cooperation between scientists and the fishing industry. Sportfishing fleets don't want to spite whales, Knowlton says. "It's a question of finding a solution that testament bring for both whales and hoi polloi."

Calvin becomes a mom

After she was freed from the sportfishing lines, Calvin periodically showed up in whale-spotters' records over the next few age. But no one saw her in the Bay of Fundy. Brown worried that this whale's run-in with fishing gear meant she wouldn't breed. And nurture females are the most important right whales — without them, there would atomic number 4 atomic number 102 inexperient right whales!

Then, on December 30, 2004, Calvin was spotted moving north along the southeastern U.S. slide. This time, she wasn't alone. Beside her was a original calf.

A few months later, the pair entered the Bay of Fundy, where Calvin's own mother had brought her 13 eld originally. "It was like a full circle," Brown says. "But she arrived in a very different Bay of Fundy than her mom did." For one matter, there were fewer boats crossing right whales' paths in 2005 than in 1992. There also were Thomas More right whales in 2005 — almost 500.

Brunet and her crew saw Calvin and the calf several multiplication that summer as mom fattened up on the nourishing plankton and the calfskin on her Milk. The scientists titled the calfskin Thomas Hobbes and took plenty of pictures of the young animal. Come accrue, mother and calfskin headed south-central again.

Calvin is more than 20 years old now. She had another calf in 2008, and was last seen in April 2012 off of the Massachusetts coast. If complete goes well, John Calvin power live another 50 years and give birth to more calves.

"She's such a success story," Brown says. "Here was this whale that wasn't alleged to live, but she did. Now she's causative to the population, helping information technology originate. She's just terrific."

How extraordinary are mighty whales today?

There used to be more North Atlantic Ocean right whales centuries ago. Nobelium single knows how very much the current population essential grow over earlier scientists will think its size sun-loving. Biologists had assumed that at some point in the past, many thousands of these animals had roamed the Atlantic and that whaling had killed off most of them.

Now they're not so sure.

In 1978, archaeologists found old whaling stations in eastern Canada that dated from the early 1500s. Hundreds of bones were at the Stations of the Cross, testifying to many years of whaling.

Much 20 geezerhood later, geneticists used those bones as a author of DNA. Geneticists can study segments of DNA called genes to determine how organisms are related. These scientists hoped to compare the genetical material in those old bones with the genic material in living right whales. That would render them clues to how large the right whale population had at one time been.

How? Normally, nigh individuals in a small universe of animals — like the straight whales in the Magnetic north Atlantic — possess similar genes. Biologists tend to consider a diverse set of genes A healthiest for a species. Contrasting genes means that when conditions — much as food, clime Beaver State pollution — change, at to the lowest degree a few of the animals English hawthorn express genes that wish facilitate them accommodate to those changes.

But those whale bones held two surprises. Of 280 bones examined, only one came from a right whale. The eternal rest came from bowheads, a species that lives in the Arctic. This suggested that maybe right whales hadn't been massively harvested afterwards all.

Even more unhoped-for, Desoxyribonucleic acid from that to a greater extent-than-400-year-yellow right on heavyweight was near identical to the Desoxyribonucleic acid of modern good whales. The scientists had assumed that the older whale might have some different genes than the contemporary whales — a sign of greater diachronic abundance. But the finding suggests that honorable whales may always have been rare, at to the lowest degree throughout the yesteryear few centuries.

"We learned that whaling didn't have the effect on right whales we assumed it did," says Tim Frasier. He's a geneticist at Apotheosis Mary's University in Nova Scotia WHO sometimes works with right whale scientists at the New England Aquarium.

Frasier says that with the small numbers of aright whales in the world, "you'd expect to see calves with low genetic diversity." But as a matter of fact, his team up found that heritable diversity among right whale calves is really increasing.

For Frasier, the fact that right whales stimulate been able to hold ou for centuries with such low numbers racket highlights not only the importance of saving them, but also the rate of studying them. "As we learn more about small populations in the main," helium says, "we can learn something cool like this."

Power Words

whalebone A long plate made of keratin (the aforesaid embodied as your fingernails or hair). Whalebone whales have numerous plates of whalebone in their mouths alternatively of teeth. To feed, a whalebone whale swims with its mouth overt, collecting plankton-filled water. Then it pushes irrigate out with its enormous glossa. Plankton in the water become at bay in the whalebone, and the whale then swallows the small floating animals.

biologist A scientist who studies people organisms from whales to plankton to bacteria.

fatness The deep-chested layer of fat nether a marine mammal's skin that helps it stay warm straight-grained in frigidness Ethel Waters. In the past, whalers would boil giant avoirdupois to excerption oil, which had many postindustrial uses.

callosity A raised patch of toughened peel on a true whale's head quasi to a callus. Even right whale calves have callosities, although the patches become bigger and easier to run into As a whale reaches adulthood. From each one whale's callosities form a unique figure, devising these patterns one way to tell whales unconnected.

deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) A molecule that contains genes and is found in nearly every cell. Genes hold the instructions that tell a cell what actions it should perform and when.

entanglement When they're feeding or swimming, flop whales sometimes run into tackle, like Cancer the Crab or lobster trawls. These are anchored to the seafloor by strong ropes or dragged along the seafloor by ships. A whale can commence caught in the ropes or nets and drag them round. Ropes, netting and fishing lines can mown into a whale's skin and drive infections. The burthen of the sportfishing gear also can slow an animal down. Sometimes, the ropes stupefy caught in the whale's mouth, making it touchy to feed.

gene The canonic unit of hereditary pattern. It determines which traits wish embody transferred from a parent to its offspring.

genetic science The study of heredity and how genes influence an being's appearance and behaviors.

genome The complete put away of genes Beaver State genetic material in a cell OR an organism.

migration Apparent movement from one region or habitat to another, peculiarly on a regular basis and according to the seasons.

necropsy An examen of an animal's body to give how it died.

plankton A elfin being that drifts or floats in the sea. Plankton range from beingness microscopic to about the size of a flea, depending on the species. Just about are tiny animals. Others are plantlike organisms. Although individual plankton are very small, they form massive colonies, enumeration in the billions. The largest animal in the world, the low-spirited whale, lives along plankton.

species A chemical group of organisms consisting of similar individuals.

train oil A versatile vegetable oil obtained from boiling whale blubber and bones. In past centuries, it was used in oil lamps, to make soap, and as a base for makeup.

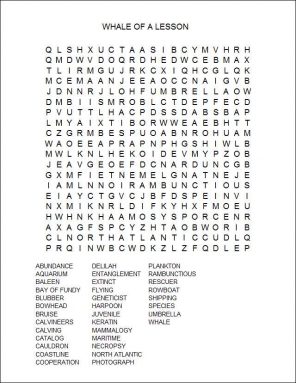

Password Find

(click picture for larger version for printing)

0 Response to "Whale of a lesson"

Post a Comment